First of all, let’s clear up a misconception about the ASHRAE Thermal Guidelines. Did you notice the word “Guidelines”? Clearly, this is not an ASHRAE Standard. This is not an industry consensus document; it was developed by IT equipment manufactures with only limited input from the rest of us. This may explain the slow adoption of more “aggressive” environmental ranges.

However the 3rd edition (2012) is a step in the right direction. It “permits” for operation at IT equipment intake conditions that some may characterize as audacious. Nevertheless, this may encourage operators to push the envelope a little extra. Some operators did not pay much attention to the previous Thermal Guidelines since they considered them too restrictive. This time around, those operators scored a point.

Let’s back up for a moment. Version 1 (2004) of the Guidelines were not too concerned about energy usage and costs. However, version 2 (2008) added some awareness of those issues. The telecom de facto standard NEBS had included energy in the analysis for decades since that standard was driven by the operators, which also paid the energy bills. For the new version, ASHRAE adopted a number of ideas from NEBS, including a widened recommended temperature range. NEBS had developed their standard based on traditional telecom-style R&D. As you might recall, the recommended envelope helps maintain high IT equipment reliability and energy efficiency whereas the allowable envelope helps avoid catastrophic equipment failures.

So what happened between version 2 and version 3 of the Thermal Guidelines? Version 2 declared the allowable temperature ranges that the IT equipment manufacturers considered appropriate for two Classes of data centers. The recommended temperature range was the same for these Classes. Some operators did not particularly like the conservative environmental envelopes, especially not when the guidelines mostly originated from the equipment manufacturers.

Version 3 on the other hand defined four Classes (rather than two) of allowable conditions that operators may want to operate within. The individual operator can now pick the environmental conditions to accommodate their business model a bit better than before and then refer to a particular ASHRAE environmental Class. Still, the recommended temperature range is the same as before and the same for all four classes.

That may not be too much progress. However, the Guidelines also provide a flowchart for determining whether more aggressive conditions could safely be implemented to gain additional energy savings. Since the Guidelines have made the decision process more complicated, this flowchart could be very helpful for small- and medium-sized data centers. The “big guys” could probably care less. They have the in-house expertise and know what is best for their business anyway.

That may not be too much progress. However, the Guidelines also provide a flowchart for determining whether more aggressive conditions could safely be implemented to gain additional energy savings. Since the Guidelines have made the decision process more complicated, this flowchart could be very helpful for small- and medium-sized data centers. The “big guys” could probably care less. They have the in-house expertise and know what is best for their business anyway.

A number of characteristics are involved in the decision making process of operating at more aggressive intake temperatures, including airflow management, sensor location, IT equipment types, use of economizers, climate factors, and data center type as well as a number of server metrics. By understanding these characteristics and metrics, the Guidelines provide assistance in establishing the appropriate data center Class and the “customized” recommended operating conditions in a particular data center. This process is a bit complicated and my guess is that many operators will default to using the standard recommended range.

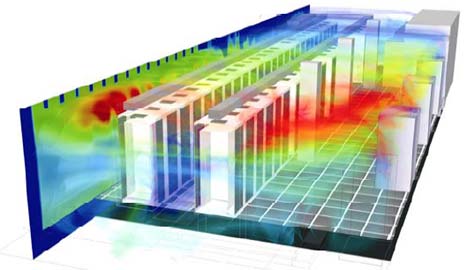

The new Thermal Guidelines include the Rack Cooling Index (RCI) for exploring higher IT equipment intake temperatures. A technical paper presented at ASHRAE in 2005 outlines the RCI, which is designed to be a measure of compliance with an intake temperature specification. A number of Data Center Infrastructure Management (DCIM) and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) vendors are using this metric to demonstrate thermal conformance.